The direction of my practice was set in 1973 while in an intensive language class at Berkeley with plans to fly off to Japan to study/practice Zen arts. In a break from flashcards, I picked up Calvin Tompkin’s The Bride and The Bachelors – Five Masters of the Avant-Garde. When class ended, I headed to New York and rented a loft on The Bowery.

My early work found inspiration in Buckminster Fuller’s newly published, Synergetics: Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking. It cemented a commitment to a conceptual framework for my art practice based on a visual exploration of spatial complexity.

In 1976, I came upon a copy of Werner Heisenberg’s Physics and Beyond: Encounters and Conversations, which recalls the physicist’s exchanges with Erwin Schrödinger, Niels Bohr, Albert Einstein, Max Planck and others. The book inspired the addition of a unifying idea and aspirational destination to the conceptual framework informing my work.

The unifying idea was based on a two-dimensional version of the Higgs Field – as I understood it at the time, an energy field permeating the universe that at its most granular level is made up of tightly packed Planck Particles. The theoretical size of a Plank Particle is set by the distance light can travel in 10-44 seconds (1 Planck Unit of Time), which is approximately 10-35 meters (1 Plank Length), a distance that’s roughly 100 million trillion times smaller than the width of a proton.

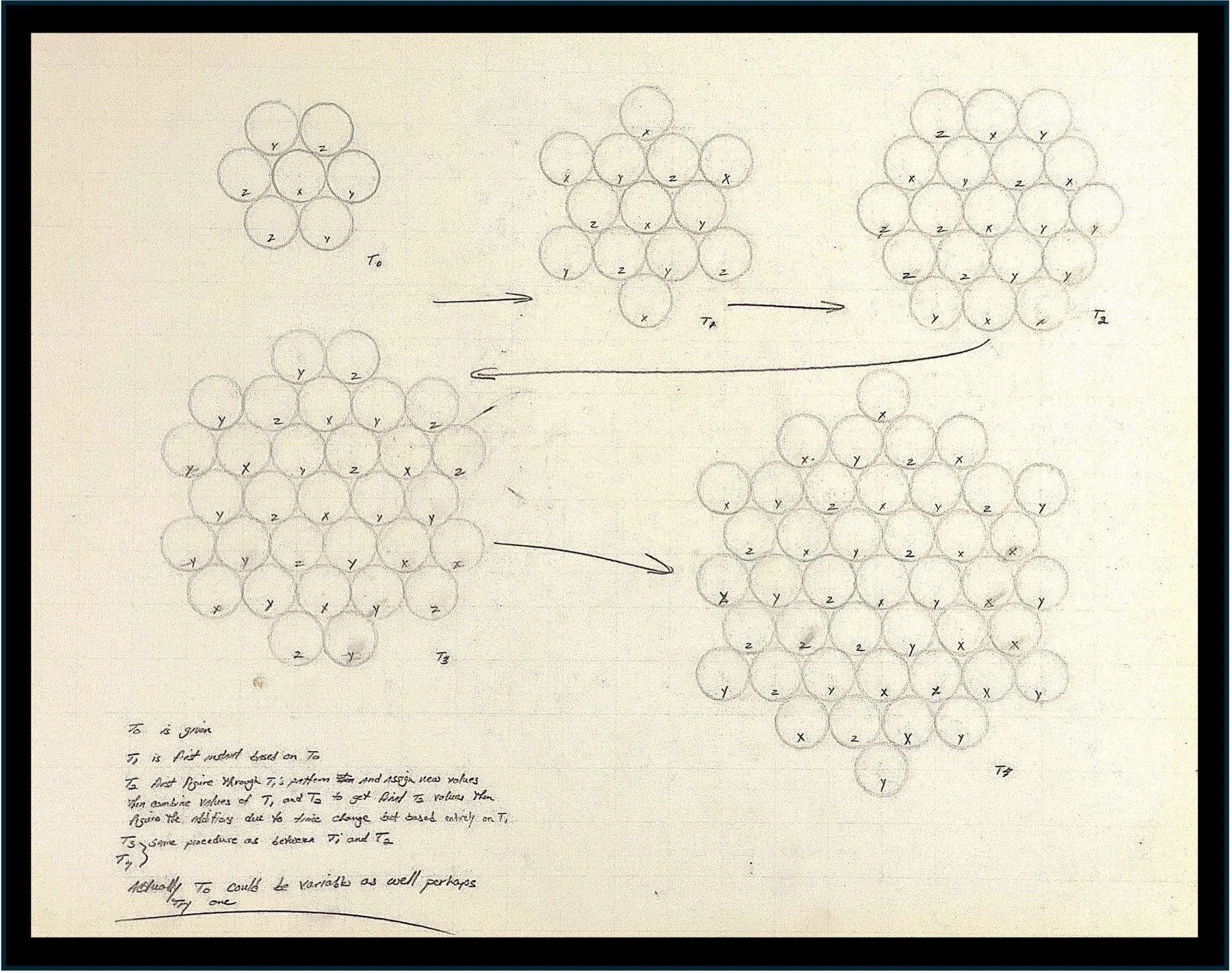

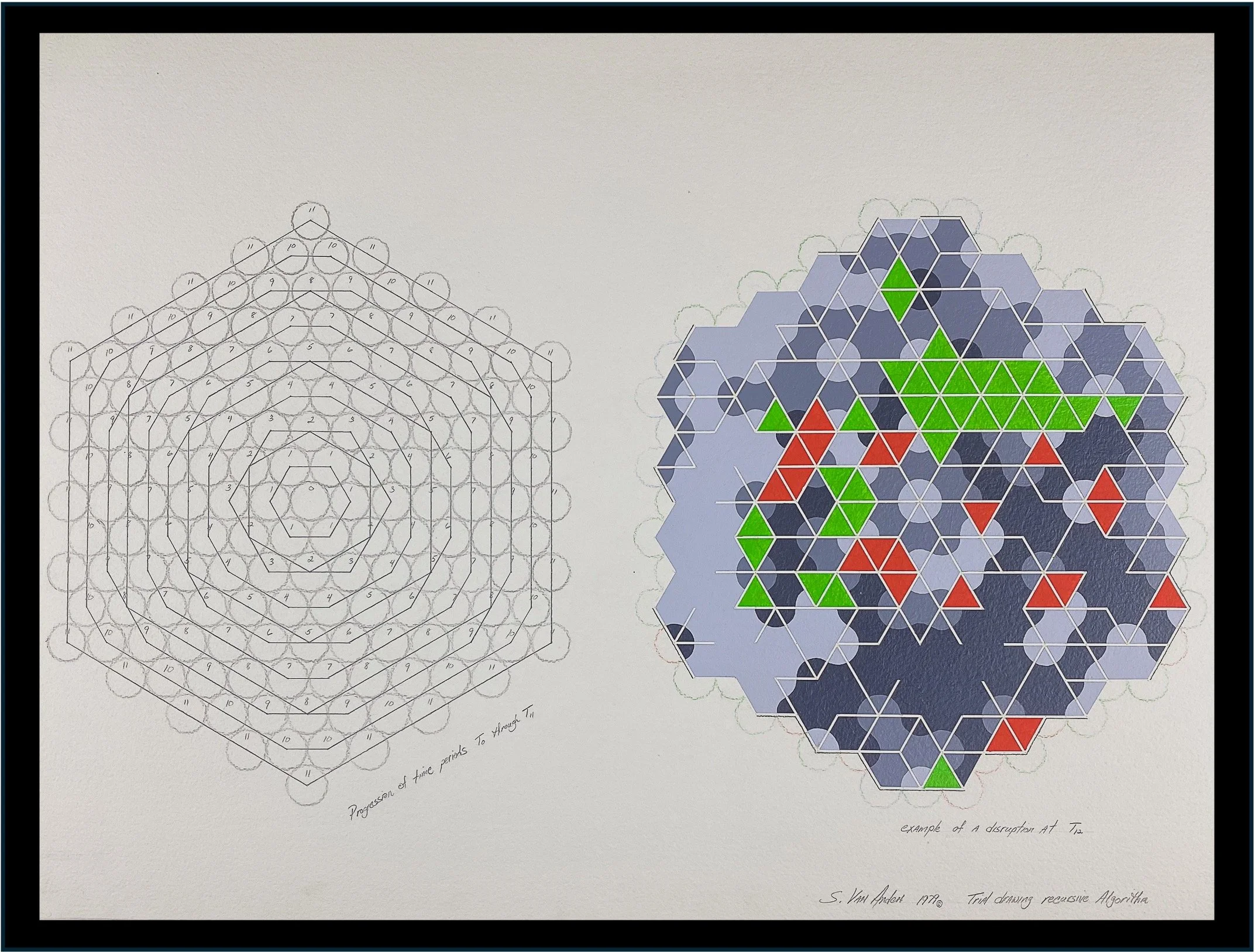

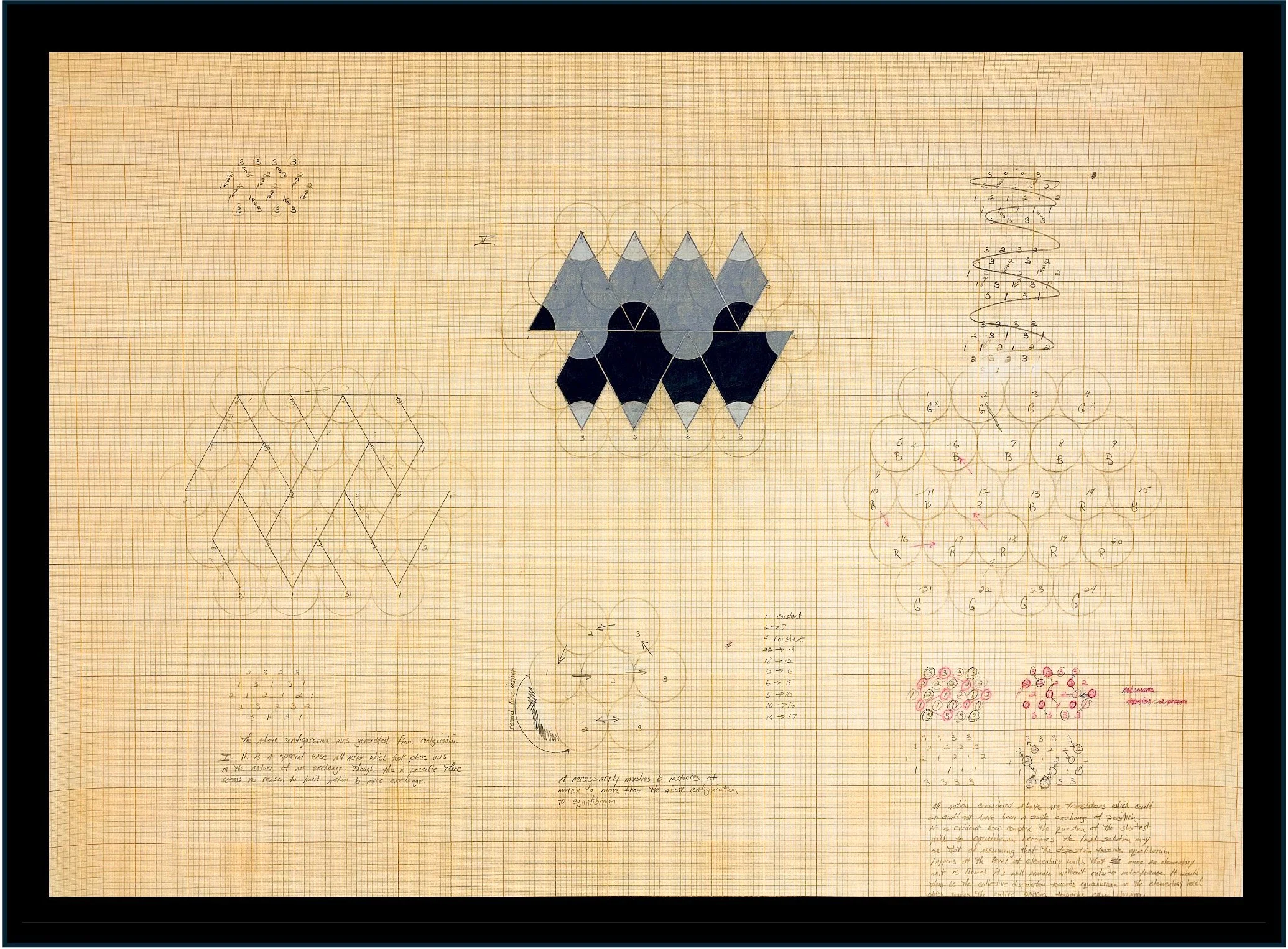

The aspirational destination I sought was an algorithm that showed how disruptions to the symmetry of a Higgs field could ripple through time and space, eventually finding equilibrium in the formation of higher order particles such as quarks and bosons.

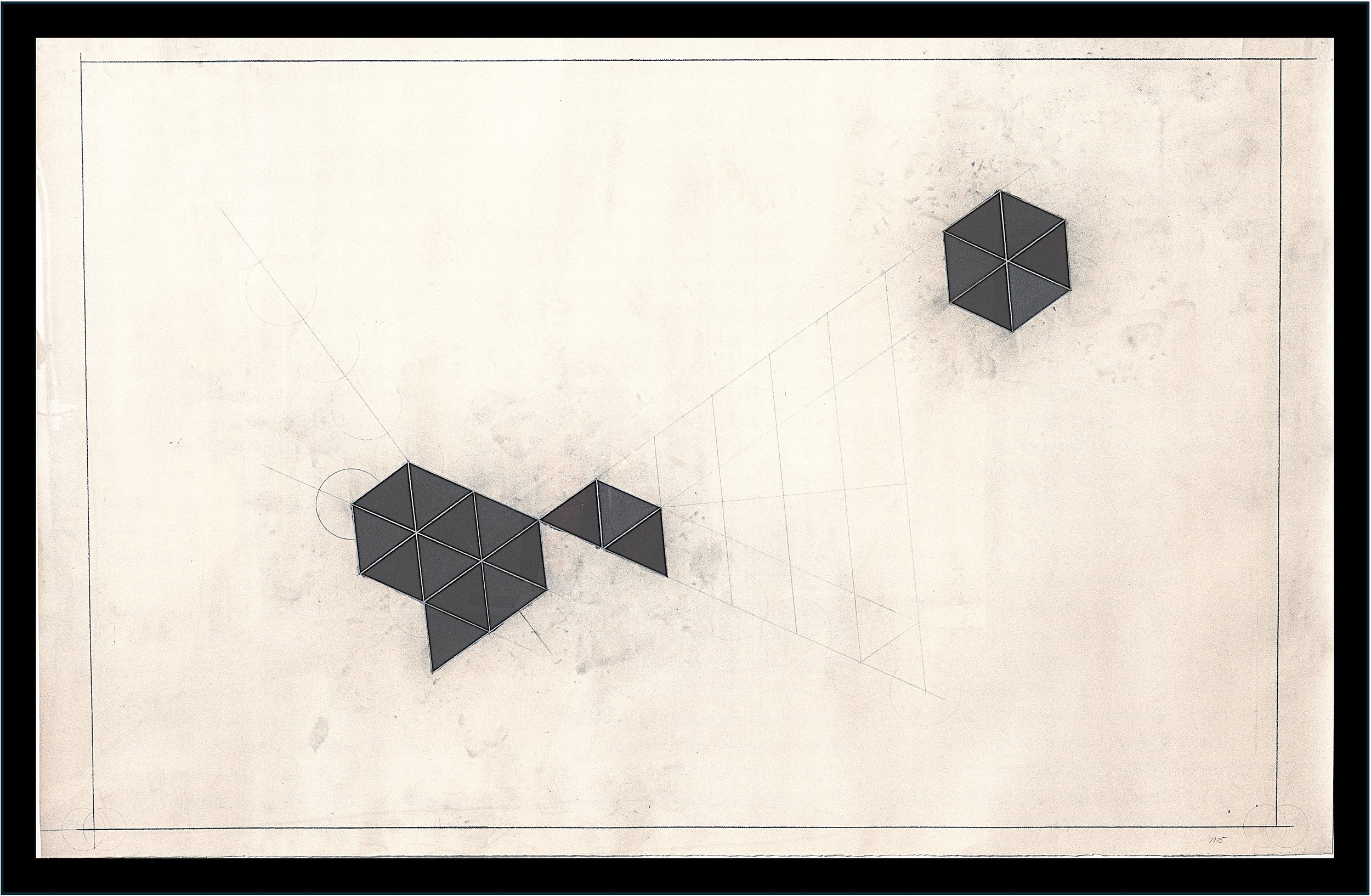

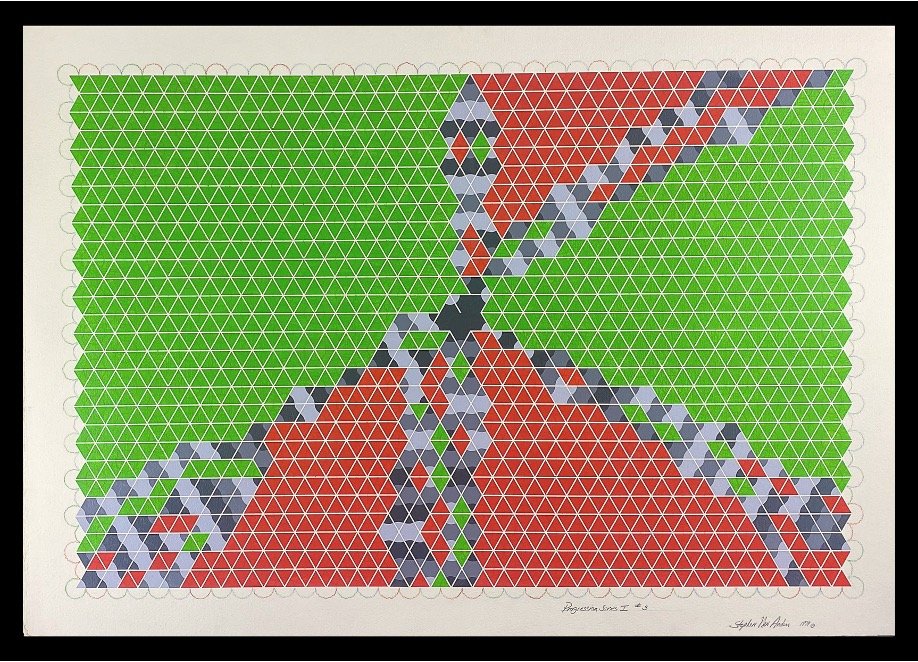

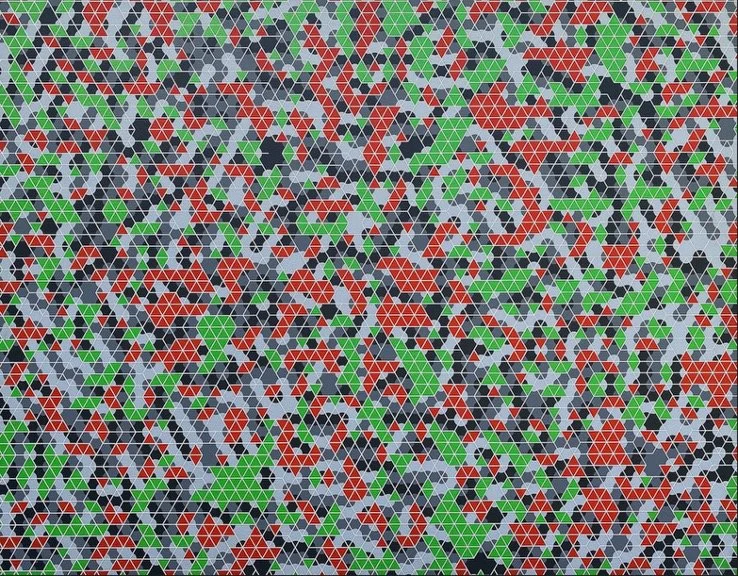

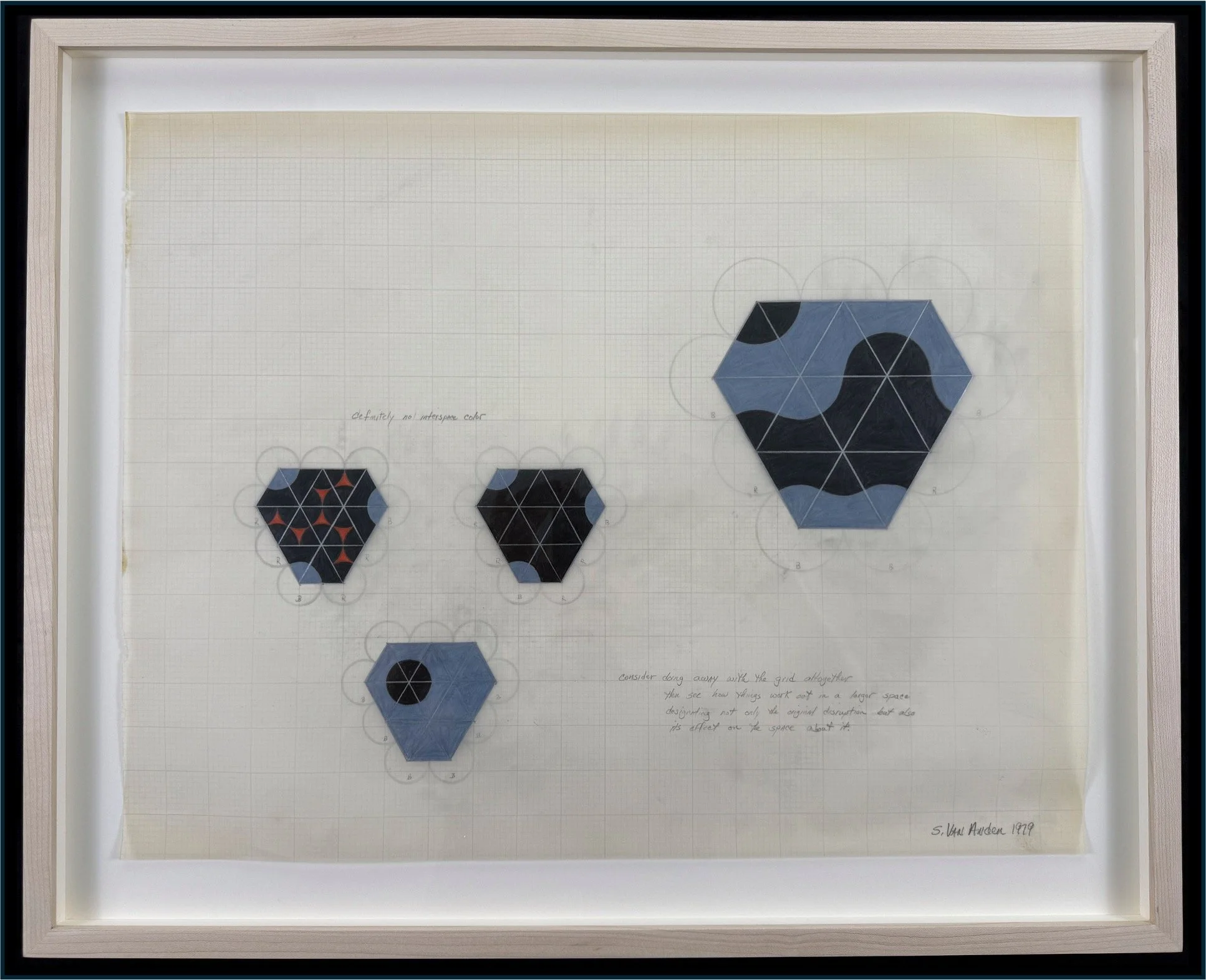

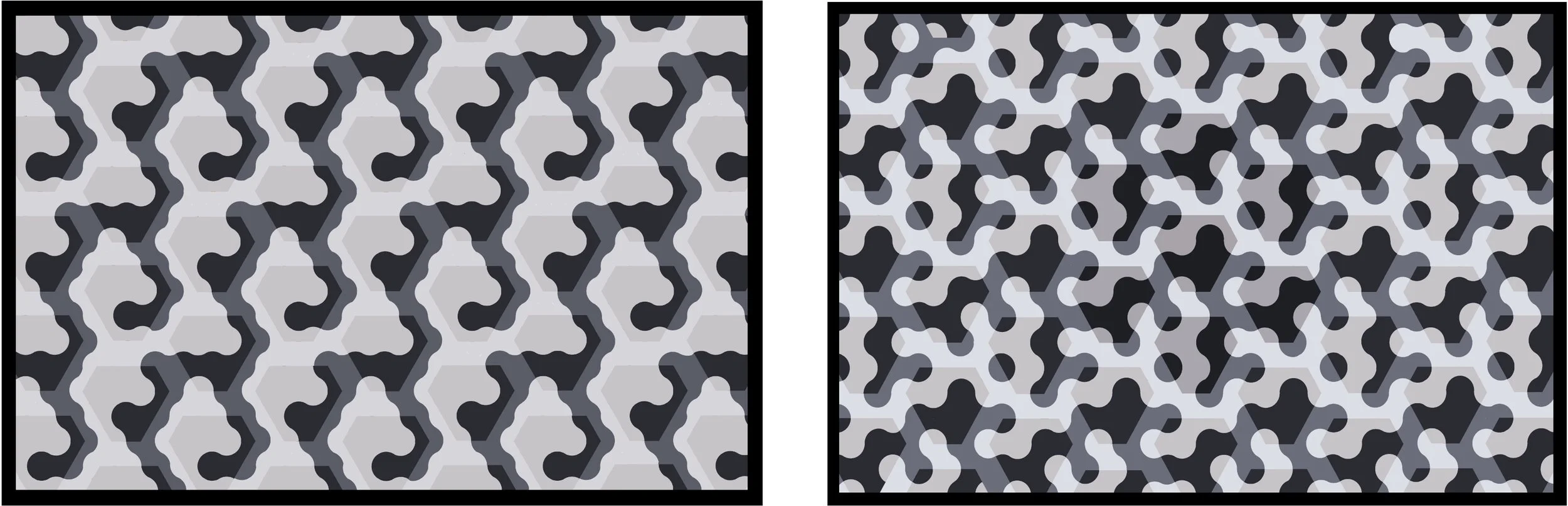

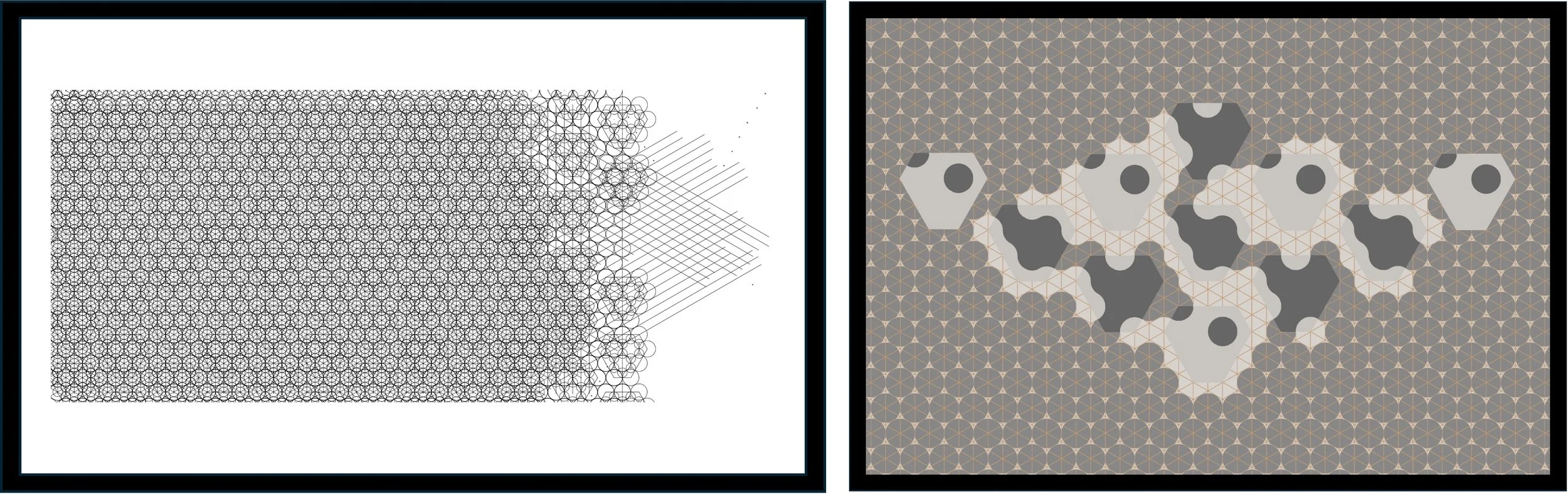

In a series of working drawings and more formal explorations, I began mapping out the effect over time that various simple algorithms had on matrices of tightly packed Plank Particles in a hexagonal grid.

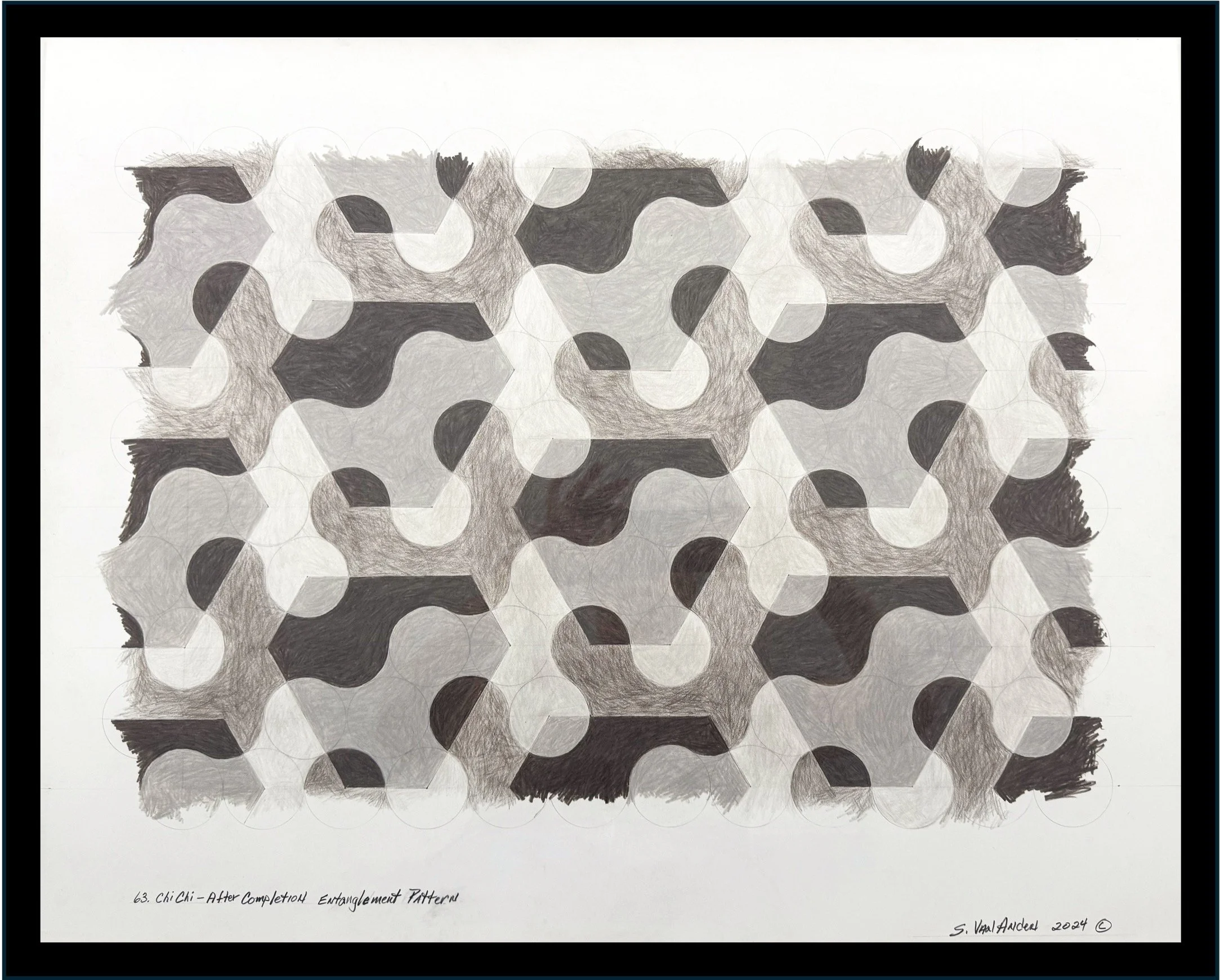

More formal, finished drawings captured how various disruptions rippled through the Higgs fields splintering it into regions of positive and negative space.

In reaction to the advent of Graffiti Art and Punk’s raw aggression – and certainly consistent with my early interest in minimalism – I sought to strip out all emotional baggage from the work.

Like Sol Lewitt’s near-identical declaration, I was determined to become nothing more than an algorithm-driven art machine.

Over time, the algorithms I developed became ever-more time consuming to work through by hand – this before the arrival of personal computers. Through a friend, I turned to running them surreptitiously, in the middle of the night at a nearby university data center. Following hours of churning, the machines would spit out pages of numbers I’d translate into drawings and larger-scale paintings. Eventually my work with computers, and a need to make a living, led me to IBM, where in 1980, I was hired as a systems engineer.

During the next number of years, while following advances in quantum mechanics and complexity theory, my art practice evolved to include abstract works that explored the emergence of order from chaos – line by line, mark by mark – in a more freeform manner.

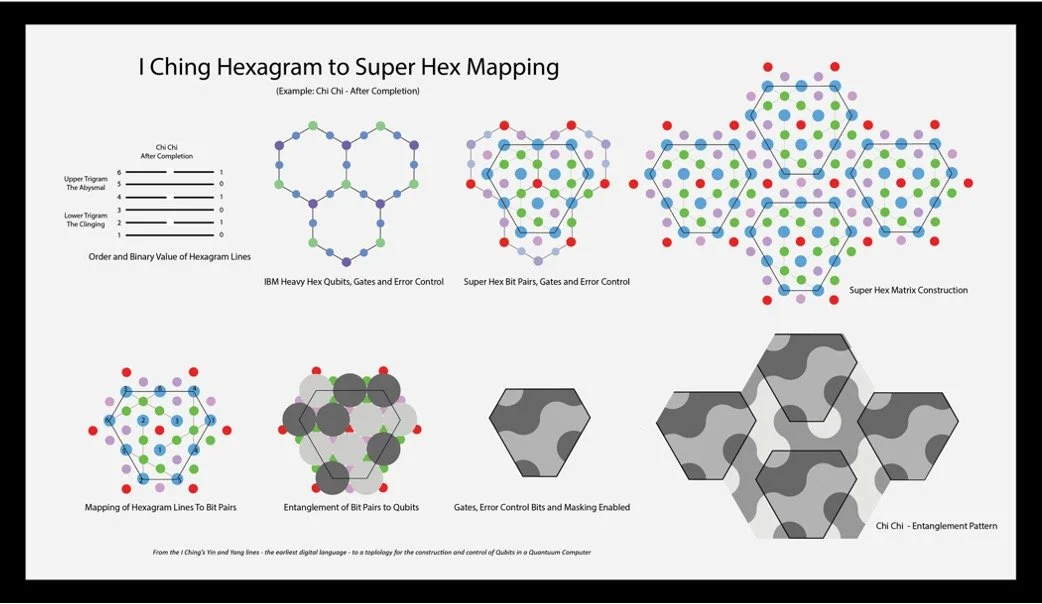

In 2024 while sorting through the contents of a flat file, I came upon a series of drawings I’d done in 1979 that explored a revisualization of the I Ching. Looking back at the work, it occurred to me that the six solid or broken lines making up each of the I Ching’s hexagrams might represent the world’s first digital language – a language that for thousands of years has been utilized to help its practitioners navigate a complex and unpredictable world.

Coincidently, I had just read a research paper on a “heavy hex” topology IBM was pursuing for laying out qubits on chips for future generations of quantum computers. I realized that recasting a hexagram’s six lines as entangled qubits in a heavy hex lattice would enable it to simultaneously represent all 4,096 permutations of the I Ching’s 64 base hexagrams.

A matrix of 64 entangled hexagrams could simultaneously hold 4,096 64 distinct states – each forming a unique tiling, or “entanglement” pattern.

I’ve just begun exploring algorithmic approaches for graphically representing the near-infinite possibilities.

If anything has changed in my art practice, it’s that I no longer am focused on finding answers to how order arises in a chaotic world. Having come full circle, I view the algorithms I work with as mere mantras for Zen-like meditations as pencil and brush glide on surfaces.

Perhaps, at last, I’ve become an art machine - others can interpret the output and search for answers.

Return to Menu